Why I’m Not Going to the Beijing Winter Olympics

I have attended 19 Olympics, Summer and Winter, usually as a radio or television commentator. The last one I missed was the Calgary Winter Games in 1988. I was granted access to the 2022 Beijing Winter Games, but I will not be going.

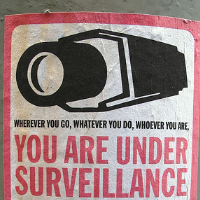

My decision has nothing to do with Covid. I believe that the “Covid bubble” created by the Chinese organizers will work. I am not going because I do not feel comfortable with the intrusive “surveillance bubble” imposed on visitors by the Chinese government.

I first visited China in 1978 when everyone dressed in blue and rode bicycles. I have visited China eight times since then, including to the Uyghur region of Xinjiang Province in 1980 and a remarkable trip to “forbidden” non-Han areas in western and southern Yunnan in 1993. The Chinese citizens I have encountered have been almost universally friendly. It’s the Communist government I don’t like. The Chinese people deserve better than to be controlled by Xi Jinping and his thugs.

I won’t go into the long list of human rights abuses committed by the Xi Jinping regime because these have been well-covered elsewhere. In 2003, I began publishing an annual list for Parade magazine of the worst dictators currently in power. In 2006, I published a book entitled Tyrants, The World’s 20 Worst Living Dictators. I included a chapter about Hu Jintao and China.

In 2007, my sons, Elijah and Aaron, and I visited Beijing and stayed in the hotel that would be used by the International Olympic Committee one year later during the Beijing Summer Games. I made use of the hotel room’s lockbox. One day, when we returned from an interview, we discovered that the lockbox would not open. I called the front desk, who sent up a surly intelligence operative. He ordered my sons and me to stand on the opposite side of the room. Then he opened the lockbox and left our room without saying a word. Nothing had been taken, but the message was clear: we’re watching you. The next day I interviewed Wang Hui, the executive deputy director of the Media and Communications Department. A veteran of dozens of interviews with foreign media, at home and abroad, she brought with a camera crew to record this one, presumably for her highlight reel. When I began asking her about human rights, she signaled her crew to turn off the camera and put it away. When I asked about the government policy of forced abortion, she claimed that forced abortions were necessary because it was an “environmental issue.” When I asked why forced abortions were not national policy, but only in regions with large minority populations, she said this was not part of her job.

At the 2008 Beijing Olympics, a colleague and I rented an apartment in a middle-class neighborhood. One night, after work, I was in the elevator with a Chinese family of tenants. Suddenly the husband said to me in English, “You should know that we have been ordered not to talk to foreigners during the Olympics.” The doors opened and he and his family exited without looking back.

At the time of the 2008 Olympics, I was posting articles to Huffington Post. I would sign in with a password and post whatever I wanted. But, during the Games, this was not possible because the Chinese government had blocked access to Huffington Post, among other sites. I had to send my article about Chinese internet censorship to an associate’s personal email account, and he posted it.

And then there was the time, at the 2016 Rio de Janeiro Olympics, when our studio was a wall away from the studios of CCTV. Our technical team discovered that the Chinese had been trying to hack into the NBC intranet.

In 2009, I launched a web site called AllGov.com which, among other things, described the United States’ economic and strategic relations with each country of the world. The Chinese hit AllGov with a huge denial-of-service (DNS) attack, worming their way into the server of a U.S. university as a go-between.

Since the rise of Xi Jinping, the crushing of individual freedoms has only gotten worse.

Now let’s compare the two Olympics held during the Covid pandemic. What is different about media access to the Tokyo Olympics in 2021 and the Beijing Olympics in 2022? As someone who had to pay my own way, I can compare them from first-hand experience.

Getting to the Olympics:

Tokyo—I booked my flights myself and then informed the organizing committee so that, upon arrival in Tokyo, they could provide transportation to my hotel.

Beijing—The Chinese government would only allow foreigners to arrive in Beijing from eleven approved airports. None of the approved airports are in North America or Oceania.

Staying at the Olympics:

Tokyo—The organizing committee gave me a list of available hotels. Using a credit card, I booked one online. Once I was there, I was able to alter my reservation (for an extended stay) without a problem.

Beijing—Credit cards not accepted. Using SWIFT, the Chinese government demanded direct access to our bank accounts. Unlike with credit card payments, once booked, payment is non-refundable for any reason. Needless to say, this had nothing to do with protecting against Covid.

Covid Testing

Tokyo—We took two Covid tests within 72 hours of departure for Tokyo. We were tested again upon arrival and many times more at the Games.

Beijing—The requirement was two Covid tests within 96 hours of departure and many tests during the Games. No problem. But there was a catch. The Chinese government also demanded the right to track each person’s health through a telephone app for two weeks before departure for Beijing. Considering post-Olympics studies showed that the Tokyo Games did not contribute to an increase in Covid cases in Japan, this is a red flag. If you believe that the Chinese added this requirement to safeguard against Covid, you have not kept up-to-date with the surveillance techniques of the Chinese government.

I recommend reading this analysis by Citizen Lab: Cross-country Exposure Analysis of the MY2022 Olympics app.

Several countries have advised their athletes and other participants to leave their computers and cell phones at home and instead to use burner phones or phones obtained upon arrival to avoid personal data being stolen by the Chinese government and to use VPNs. If you think the Chinese won’t hack into these phones and VPNs too, you’re naïve. According to a recent review of Chinese procurement documents by The Washington Post, the Xi Jinping government invited bids for a software program “that mines Twitter, Facebook and YouTube for data on ‘well known Western media journalists’ and other “key personnel from political, business and media circles.’” And that’s the tip of the iceberg.

You might say that the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) does the same thing the Chinese are doing. Absolutely true. Indeed, if I were elected president of the United States, during my first week in office, I would fly to Utah and visit the NSA’s Intelligence Community Comprehensive National Cyber-security Initiative data center to see for myself what dossiers they have on Americans and others.

However, there is a big difference between what the NSA does and what the Chinese government does. The NSA, to the best of my knowledge, has never opened one of my hotel lockboxes. The NSA has never blocked my access to a web site. And the NSA has never tried to stop me from posting whatever I want on the internet.

For those of my media colleagues who are going to Beijing for the Winter Olympics, more power to you. But as you use your VISA card to buy coffee or food or souvenirs, ask yourself to what that card is connected and what information can be sucked from it. The same goes, of course, for your telephone or your computer. From The New York Times: “All the information you are transmitting can be intercepted, particularly if you are on an untrusted network like a coffee shop or hotel Wi-Fi service,” said Jeffrey Knockel, a research associate with Citizen Lab and one of the authors of the report. Sensitive information lifted in this way could be used for identity theft, Dr. Knockel added.

If you’re going to stick to reporting about the athletes and the competitions, other than the lifting of all your data, I’m sure you’ll be fine. But if you’re thinking of saying or writing anything critical of Xi Jinping or the Chinese government, keep in mind this warning from the United States State Department (emphasis added): “The PRC [People’s Republic of China] government arbitrarily enforces local laws, including by carrying out arbitrary and wrongful detentions and through the use of exit bans on U.S. citizens and citizens of other countries without due process of law….In most cases, U.S. citizens only become aware of an exit ban when they attempt to depart the PRC, and there is no reliable mechanism or legal process to find out how long the ban might continue or to contest it in a court of law.”

If you wish to reach me for fact-checking or for an interview, if you will be outside Beijing, I’ll be ready to help. But if you are in Beijing or have already activated your My2022 app, please contact me through a third-party who is outside the “surveillance bubble.”

Have a good time, and I hope to see you all in Paris in 2024.

-David Wallechinsky

- Top Stories

- Unusual News

- Where is the Money Going?

- Controversies

- U.S. and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Latest News

- Can Biden Murder Trump and Get Away With it?

- Electoral Advice for the Democratic and Republican Parties

- U.S. Ambassador to Greece: Who is George Tsunis?

- Henry Kissinger: A Pre-Obituary

- U.S. Ambassador to Belize: Who is Michelle Kwan?

Comments